The sun provides the energy necessary for life on Earth. The environment and living things are being impacted by global warming. Roughly 50% of the light that enters Earth’s atmosphere is absorbed at the surface and reflected upward as infrared heat after passing through clouds and air. The surface is subsequently heated to an average temperature of 59 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius), which is sufficient for life after around 90% of this heat is absorbed by the greenhouse gases.

Is the sun to blame?

How do we know that changes in the sun aren’t to blame for current global warming trends?

Several satellite devices have been directly measuring the sun’s energy output since 1978. During this time, there appears to have been a very modest decrease in solar irradiance, a measurement of the amount of energy the sun emits, according to satellite data. Thus, the warming trend that has been shown over the past 30 years does not seem to be caused by the sun. Sunspot records and other so-called “proxy indicators,” including the amount of carbon in tree rings, have been used to estimate solar irradiance over longer periods. According to the most current assessments of these proxies, variations in solar irradiance are not likely to be responsible for more than 10% of the warming observed in the 20th century.

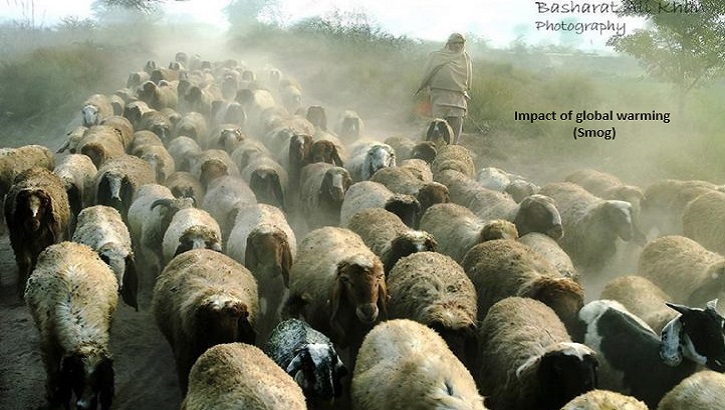

Global warming and livestock

Methane, which makes up 16% of all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide resulting from human activity, is the second most significant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide. Methane has a 21-fold greater potential for global warming than carbon dioxide. After rice fields, ruminant methane production has been identified as the single biggest source of anthropogenic CH4. Methane is naturally released by livestock throughout their digestive processes. Billions of bacteria, methanogens, protozoa, and fungi live in the rumen, where they break down the grain to create methane, carbon dioxide, ammonia, and volatile fatty acids (VFAs). Animals use volatile fats (VFAs) as a source of energy, whereas gases are expelled by the mouth and the rectum. Cattle can produce 250–500 liter of methane per day per animal and generally lose 2–15% of their ingested energy as eructated methane. Approximately 100 million tonnes of methane are produced annually by cattle, and when these emissions are multiplied by the number of animals worldwide, the total emissions from cattle represent 15% of all methane emissions. Therefore, cutting back on methane emissions from cattle, especially from cows, is an excellent strategy to reduce methane emissions globally. However, there are both financial and environmental advantages to reducing ruminant methane leaks. reduced methane levels translate into reduced atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. Additionally, less methane equals better animal production efficiency and higher farmer revenue. The content of the animal feed can be changed to regulate a higher level of methane output. Changing the feed composition, either to reduce the protein percentage which is converted into methane or to enhance the meat and milk yield has been considered the most efficient methane reduction strategy. Enhancement in the overall quality of animal feed may prove helpful in maintaining meat and dairy production at the same level with fewer animals and so less total methane emission.

Natural sources, such as wetlands, as well as man-made ones, including rice fields, biomass, ruminants, etc., all emit methane into the atmosphere. To reduce greenhouse gas emissions globally and improve animal performance through increased feed conversion efficiency, it is often necessary to mitigate methane (CH4) losses from ruminants. Monogastric animals—such as pigs, chickens, rabbits, etc.—contribute extremely little methane to the atmosphere as compared to ruminant emissions. The fact that ruminant animals may create 250–500 L of methane per day makes it crucial to research and attempt to reduce the emissions from cattle.

Read: Consider Supporting the PakSci Mission Community this Giving Tuesday

Energy losses and methane production in the digestive tract of ruminants:

The synthesis of the methane in ruminants reflects energy loss and it is due to the reduction of the carbon dioxide by methanogenic bacteria. After the feed is digested in the rumen, some of the energy is lost in the form of heat or methane, giving a production of methane utilizing between 11 and 13% of the digestible energy

Dietary manipulation

Roughages (Forage type and quality):

The composition and quality of forage along with the level of intake significantly influences the rumen fermentation. Ruminants fed low-quality roughages could release a large amount of methane. Feeding crop residues to ruminants is a common practice in many Asian countries due to which methane emission from ruminants especially cattle is significant. 15% reduction in methane production by increasing the digestibility of forages and 7% by increasing feed intake. Grinding and pelleting operations of roughages decrease methane production by improving the passage rate and reducing the time of feed. The shifting of animals from low to high digestible pasture significantly reduced methane production per gram of live weight gain. The use of forages meant to improve animal performance can reduce methane emissions per unit of feed intake. Importantly, pasture improvement can be a good choice if fewer animals are used

Concentrates:

The methane production differs depending on the different types of carbohydrates that are fermented. The fermentation of cell wall fiber will lead to the production of a higher proportion of acetic acid in the rumen. In contrast, starch fermentation gives a higher proportion of propionic acid due to the lowered pH in the rumen which causes changes in the ruminal micro-flora by an increase of amylolytic microbes and a decrease of cellulolytic microbes.

The end products of the fermentation the Volatile Fatty Acids (VFA) are mainly acetate, propionate, and butyrate, we can also find valerate, isovalerate, isobutyrate, and caproate but in very low proportions. They are also the main source of energy for the ruminants, and this energy is used by the lactating cow to produce milk and body fat, but not all VFAs have the same degree of efficiency. Propionic acid fermentation is more efficient in the use of energy than acetic and butyric acids which have a large loss of methane. The type of VFA produced by the animal influences the release of methane and hydrogen, increasing the release of methane when the relation of ruminal VFA [acetic acid+butyric acid]/propionic acid increases there is a negative correlation between the proportion of concentrate and methanogenesis. A significant reduction in methane production was reported in young bulls fed with a diet containing more than 40% starch. A diet comprising 45% starch decreased methane production by 56% compared to diets containing 30% starch without affecting animal health.

The inclusion of starch in the diet has a significant impact on changing ruminal pH and microbial populations.

As concentrate contains more soluble substances, the addition of concentrate to animal diet changes the composition of partial short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) from higher to lower acetate production and more propionate. Similarly, milk quality is negatively affected if concentrates exceed 50% which limits the use of concentrates to lower methane emissions in the dairy sector.

Cereal grains with a high proportion of starchy endosperms like wheat, barley, or oats have an easier and faster fermentation giving less methane than those that have a lower proportion like maize, and sorghum.

Lipids:

Lipids and lipid-rich feeds are among the most efficient and emerging options for methane mitigation. Lipid inclusion in the diet reduces methane emissions by decreasing fermentation. Saturated medium-chain fatty acids, C10-C14, also lead to methane reduction. At ruminaL temperature, an increasing chain length of medium chain fatty acids seems to reduce their efficiency in inhibiting methanogens and methane formation due to lower solubility reviewed the practical application of lipids to reduce methanogenesis. Oil supplementation to diet decreased methane emission by up to 80% in vitro and about 25% in vivo. The toxic effects of certain oils on rumen protozoa contributed to reduced methane production. The addition of canola oil at 0%, 3.5%, or 7% to the diets of sheep reduced the number of rumen protozoa by 88–97%. The detrimental impact of unsaturated fatty acids has also been reported. Coconut oil is a more effective inhibitor followed by rapeseed, sunflower seed, and linseed oil.

The inclusion of sunflower oil in the diet of cattle resulted in a 22% decrease in methane emission. However, fats and oils may pose numerous negative impacts to the animals. Dietary oil supplementation caused lower fiber digestibility. High cost and the negative impact on milk fat concentration are some of the limitations of oil supplementation.

Miscellaneous activities to reduce methane emission:

Increased milk yield:

The milk yield also influences the production of methane, when milk yield increases, the methane per kilo of milk decreases. This is logical and can be explained by the fact that the energy needed for maintenance is considered approximately the same for the animal irrespective of production level. The methane production that originates from maintenance needs is therefore also estimated to be the same for an individual animal of a specific weight. When the milk yield increases, the DMI also increases but not in the same proportion. With the increased milk yield, there is more milk to carry the “burden” of maintenance needs and methane per kg milk will decrease. Thus, with increased milk yield the methane produced in absolute terms will increase somewhat but the methane per kg of milk will decrease.

Using of feed additives:

Some additives like ionophores and particularly monensin have been studied. Monensin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic obtained from actinomycete Streptomyces cinnamonensis used in some countries. It is not allowed in the European Union but it is used in the United States. Its main action is to change the fermentation from acetate to propionate which leads to the decrease of methane production. However, the widespread use of antibiotics can lead to future problems with bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics and the environmental and economic advantages of using antibiotics to decrease methane production must be weighed against the negative health effects of increased resistance.

Feed intake level:

The level of intake can also affect methane production when an animal increases its intake, the percentage of gross energy lost in the form of methane decreases

The role of human activity

In its Fourth Assessment Report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of 1,300 independent scientific experts from countries all over the world under the auspices of the United Nations, concluded there’s a more than 90 percent probability that human activities over the past 250 years have warmed our planet.

The industrial activities that our modern civilization depends upon have raised atmospheric carbon dioxide levels from 280 parts per million to 400 parts per million in the last 150 years. The panel also concluded there’s a better than 90 percent probability that human-produced greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide have caused much of the observed increase in Earth’s temperatures over the past 50 years.

They said the rate of increase in global warming due to these gases is very likely to be unprecedented within the past 10,000 years or more.